Monitoring Third Party Payments

One of the most challenging tasks for ophthalmology practices is the business process of sending thousands of fee-for-service claims (for both medical and surgical services) to third-party payors and of ensuring proper payment.

In this issue of Watching your Bottom Line, we’ll examine some of the methods that practices have found successful for monitoring payments and for ensuring that every payment is received when promised and in the promised amount.

What are some of the ways that a health lan may pay less than promised?

Non-response. You send a claim for services, and there is no response from the payor.

Delay. The claim is returned with a request for additional information.

Down-coding. You send a claim for an E&M service, and a reduced payment is sent with a notice that the level of service has been reduced.

Reduced Payment. The claim is paid on time with no indication that the payment is anything but normal, although the payment level is less than the contracted allowable payment.

Tools

Assuming you are receiving the best contract rates, what systems do you need to monitor if you’re getting what you’re promised?

Contracts-payment levels and terms by plan. You can’t determine if a payment is adequate without knowing the allowable payment levels and the timeliness of payment as specified in the contract and governed by state law. These levels should be displayed on a table available to the staff member posting payments, or loaded into a computer system that has the ability to check payments against specific fee schedules.

Denials log. Each time that a claim is denied or downcoded, keep a record in the denials log of the code charged, the health plan, and the reason. In addition to identifying health plans that inappropriately deny claims, the log will help you identify repeated problems with inaccurate coding, patient demographics, and insurance plan assignments.

Reporting. If your system has the ability to load allowable payment levels into multiple schedules, this function should be used.

Identifying Problems

As each payment is received, it should be checked for accuracy using your system’s ability to load allowable payment levels into multiple schedules.

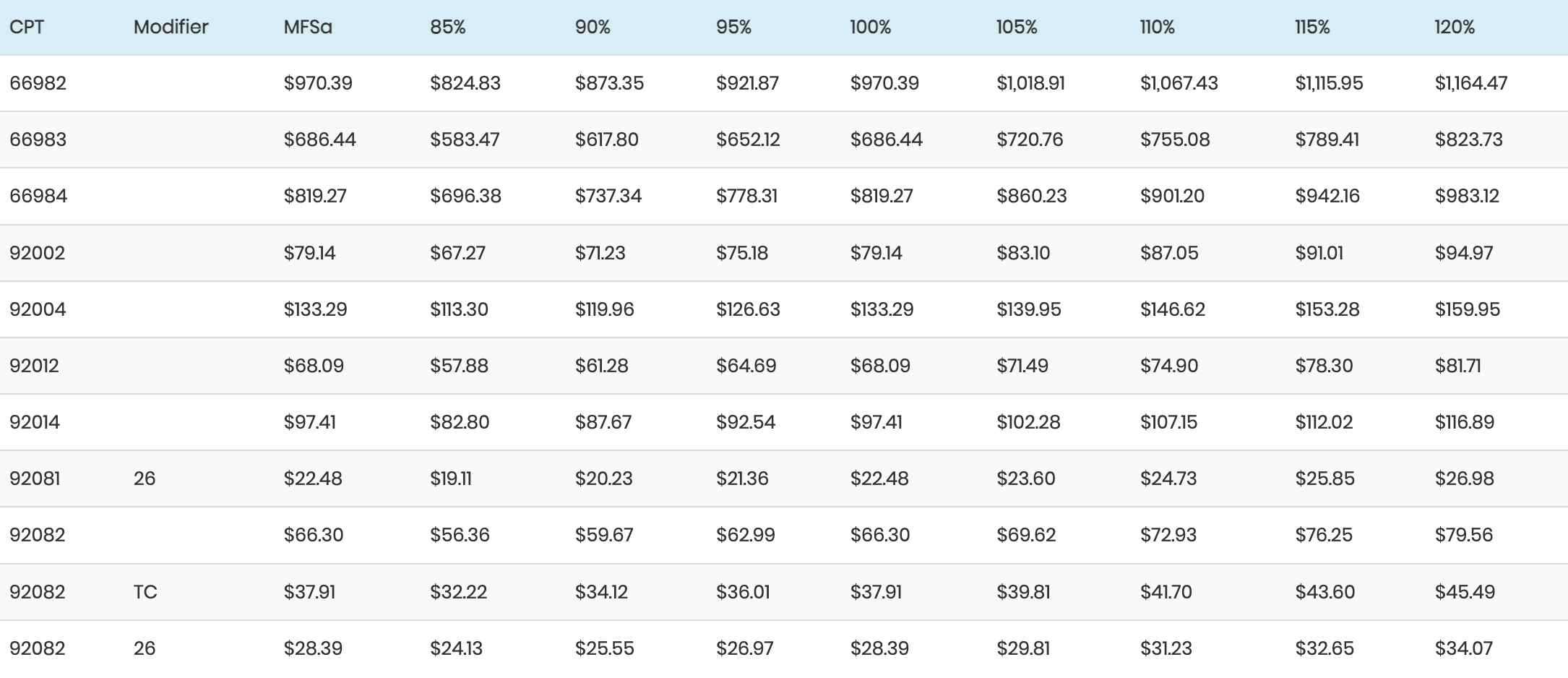

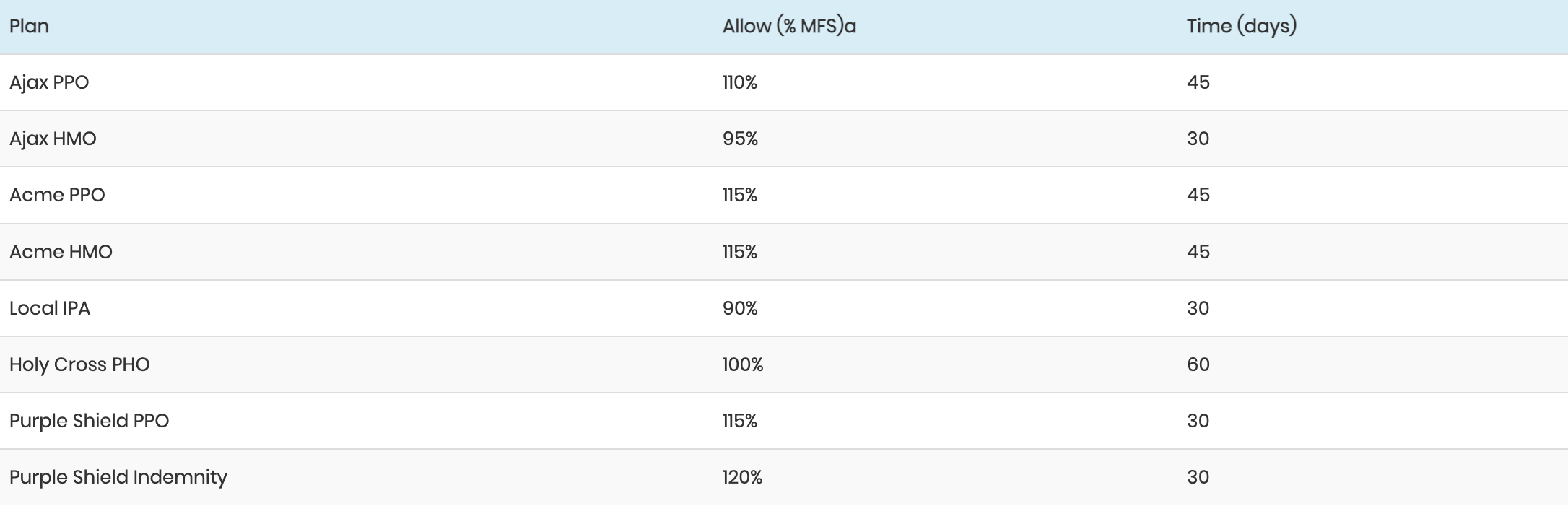

Plans tend to gather around a statistical mode of payment. For instance, most plans in a market will pay at a similar multiple of the Medicare fee schedule. If your system allows, you can load fee schedules at 90%, 95% 100%, 105%, 110%, 115%, and 120% of the MFS, and then point or link each insurance plan to the appropriate schedule.

If your system does not have the ability to load multiple fee schedules, or if the implementation of that function is difficult and cumbersome in your system, use a manual system. Develop a spreadsheet of allowable payments and an accompanying spreadsheet of plan payment levels (see below). Both spreadsheets should be available to each staff member posting payments.

A – Sample MFS data

Note that in the case of plans that pay at a percentage of charges, the allowable can be calculated as follows: Practice fee schedule as a age of the MFS = 150% Contract calls for payment at 80% of charges 80% of 150% = 120% of the MFS

The contract’s commitment for timeliness will drive your monitoring of accounts receivable (AR). Run an AR for each plan, by patient account, within 5 days after the promised payment time. For example, in the table above, Acme promises payment within 45 days. Each month, an AR report by plan that has accounts unpaid after 60 days should be followed up. Repeated non-response should trigger a call and letter to the plan reminding them both of their timeliness contractual obligation and of any prompt-payment regulations in your state. Continued tardiness warrants a repeat letter with copies to the state agencies responsible for that type of plan. It is important that you have a system in place to identify claims that are ignored by the plan.

Retrospective Reporting

In order to assess your collections by plan, you can either conduct a manual or automated review.

For a manual review, collect EOBs (Explanation of Benefits forms) covering a one-month period and compare each payment to the expected amount. Select one or two payors to review each month, beginning with those representing the highest age of your charges or those with a high index of suspicion for inadequate payments (or both).

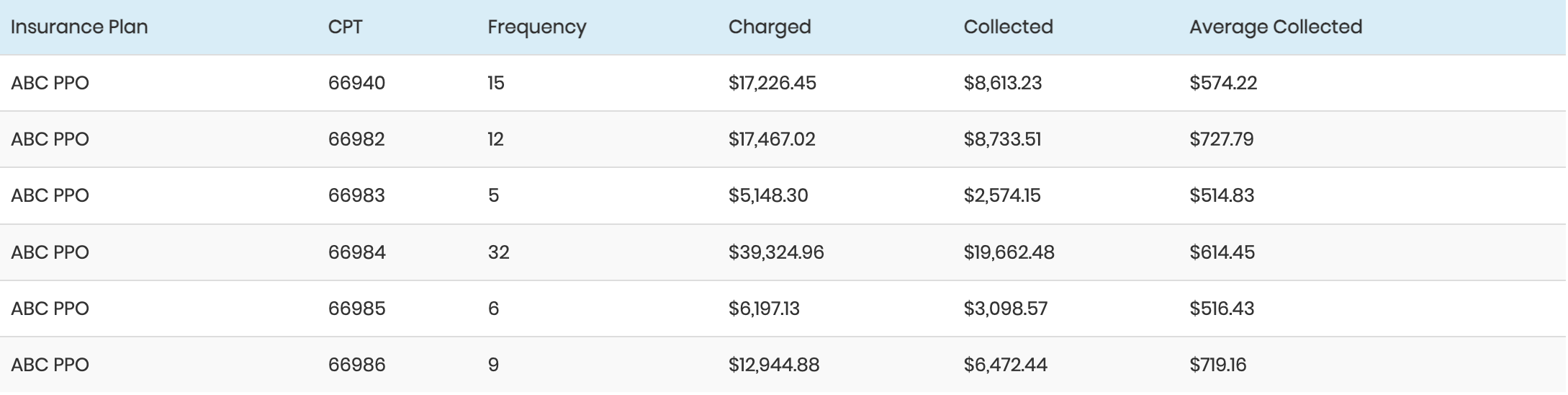

If your practice management computer system has flexible reporting, you can use this function for a more comprehensive and accurate review. The report you want is one stratified by insurance plan and then by payment by CPT code. The following is an example:

Your system may provide an additional column for the expected amount, based on a fee schedule in the system for that plan.

As an alternative, you can export the report to a spreadsheet program if your system is capable of exporting data. A workaround to use if your system cannot export data is to print the report on a laser printer, and using a scanner (now available for well under $100) and a document-handling software package, scan the report. Using the software’s optical character-reading capability, place the data into a spreadsheet.

With the data in a spreadsheet, add the additional columns needed for the analysis:

In this example, the practice’s fee schedule is at 150% of the MFS. This payor, after a contract renegotiation, agreed to pay 110% of the MFS. By dividing the allowed amount (110%) by the practice fee (150%), the expected collection of 73.33% was derived. The payor, although agreeing to an increased reimbursement, was still paying at an old (and lower) rate. These administrative errors in the payors’ claims-processing operations are common, and it is worth a significant amount of revenue to the practice to monitor the payors.

In ordering the report, specify a time period of charges for which all (or at least most) payments have been received. For example, if the plan’s allowable payment changed on April 1, 2001, and you ordered the report in December of 2001, you should include only charges from April 1 through September 30. This will ensure that most claims have had at least 90 days to be paid.

At this point, you need to really understand the way your system reports. For instance, many systems have a well-designed report that provides the data as described above, but provides no way to isolate only those claims with a zero balance. By including claims that have not been completely paid, the collection ratio is not a true representation of the payor’s performance, since some partly paid or completely unpaid claims are represented.

Actions After the Analysis

If you find that a plan is not paying at the agreed level, the first step is a call to provider relations. Armed with documentation of the increased rates (or of the original rates if there was no increase), ask the plan for a correction for future claims, as well as a retrospective payment for all claims to date, to make up the deficiency. Continue monitoring payments from that payor to ensure that the correction is made and that you receive payment for past deficiencies.

If the payor cannot or will not pay the contracted amount, the next step is to send copies of all relevant correspondence to the state agency that is responsible for the type of insurance plan in question. Similar steps should be taken if the payor’s payments are chronically late (later than contracted or allowed by state regulations or law).

Implementation Summary

Collect expected payment data.

Request increases for low-paying plans.

Implement a denials log to ensure that errors are not made in your practice and to identify problem insurers.

Develop tools (using either the computer system or a manual system) for the payment-posting staff to determine real-time payment adequacy at posting.

Develop a reporting system to identify tardy or inadequate payments.

Follow up with payors.

Holding insurance plans accountable for the payments they have contractually agreed to is not only satisfying but can be lucrative for the practice. Some practices that have implemented monitoring systems have experienced 5% to 15% increases in overall collections. These income increases make the monitoring effort worthwhile.

Ron Rosenberg, PA, MPH, Author

Practice Management Resource Group